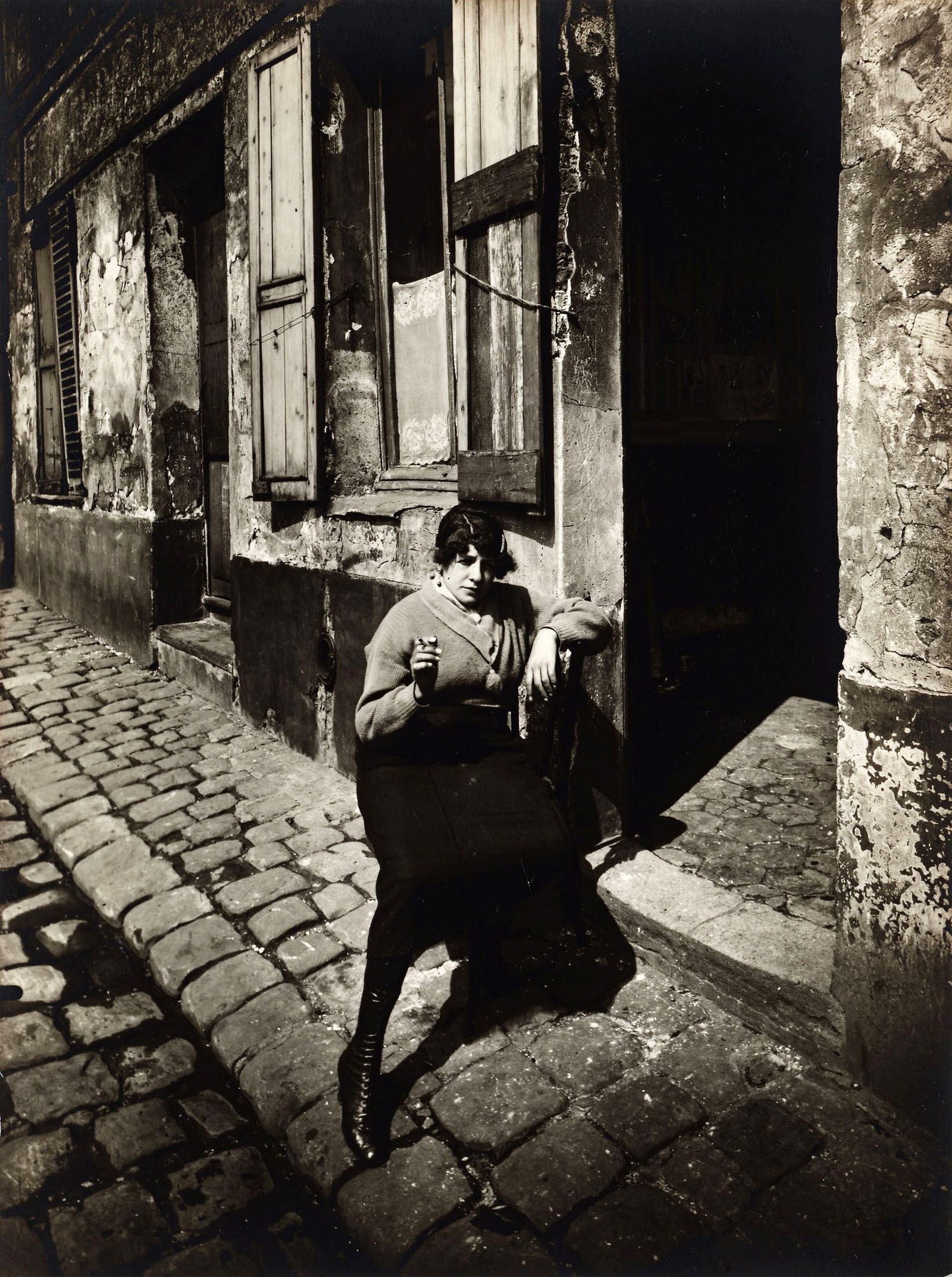

Photos: The urban facelift of Paris was calculated and devastating

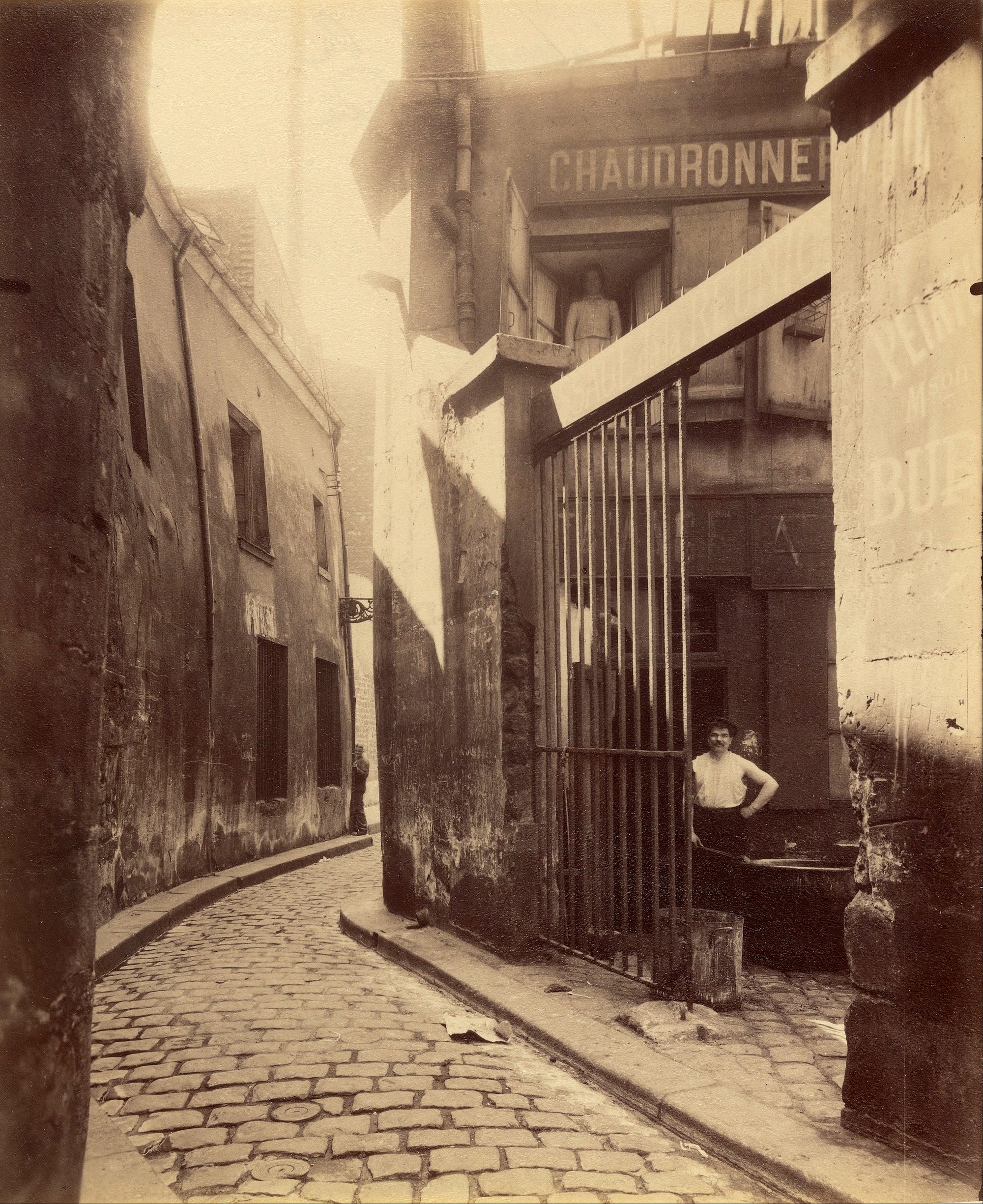

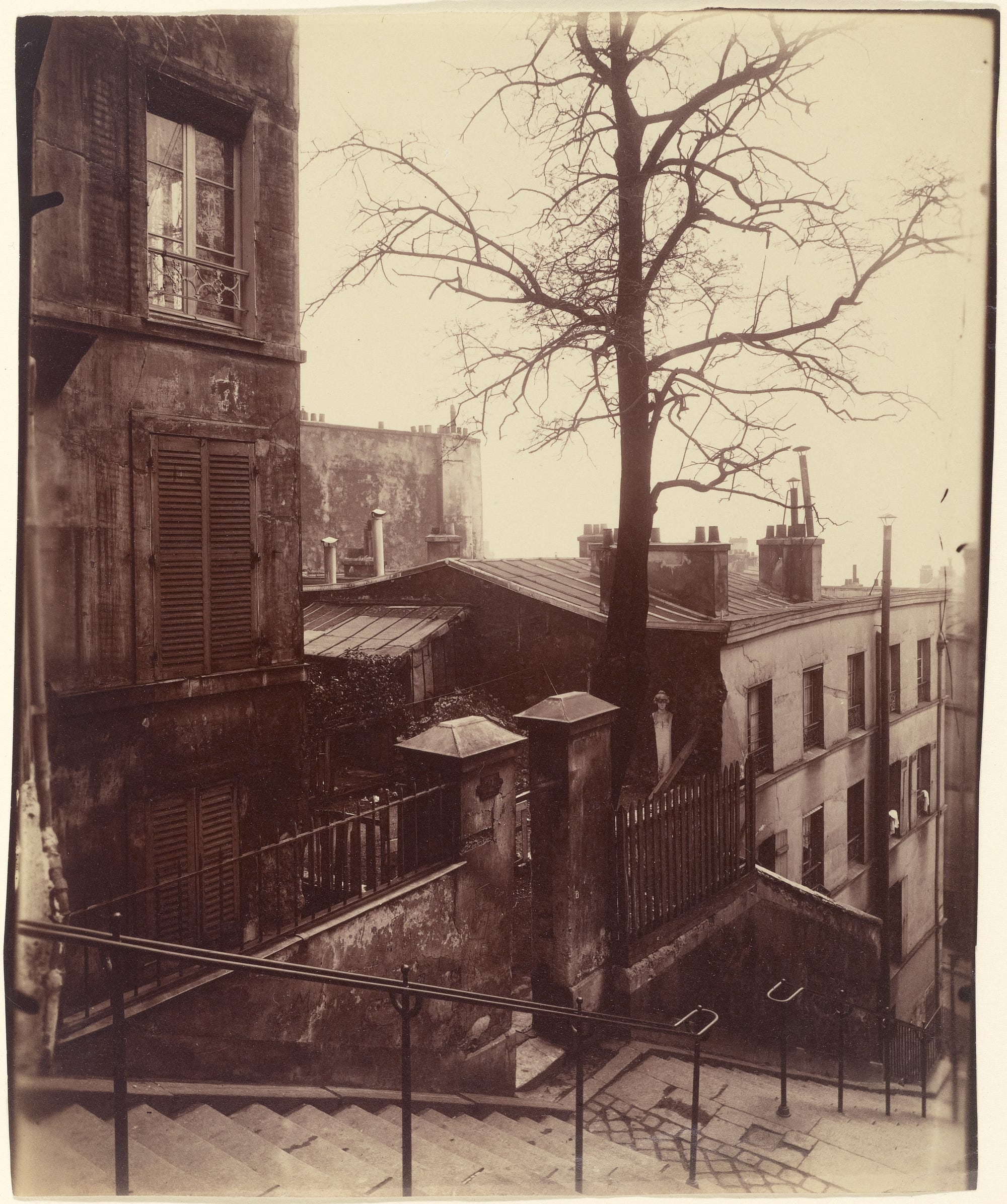

Hecrept through the streets in the early-morning hours. Eugène Atget was on a mission to preserve the narrow, twisting streets of crumbling apartments and dusty shops before they disappeared. Many already had.

By 1890, when the former traveling actor returned home with a throat infection and a large-format dry plate camera, Paris had been undergoing a metamorphosis for almost 40 years. Tangled neighborhoods filled with old three- or four-story buildings of wood and plaster were being torn down, replaced by geometric boulevards and towering stone apartment blocks. Brick warehouses gave way to open plazas and small parks. Sewers were being rebuilt, carts could easily navigate the improved streets, and there was room to breathe, but not everyone was happy.

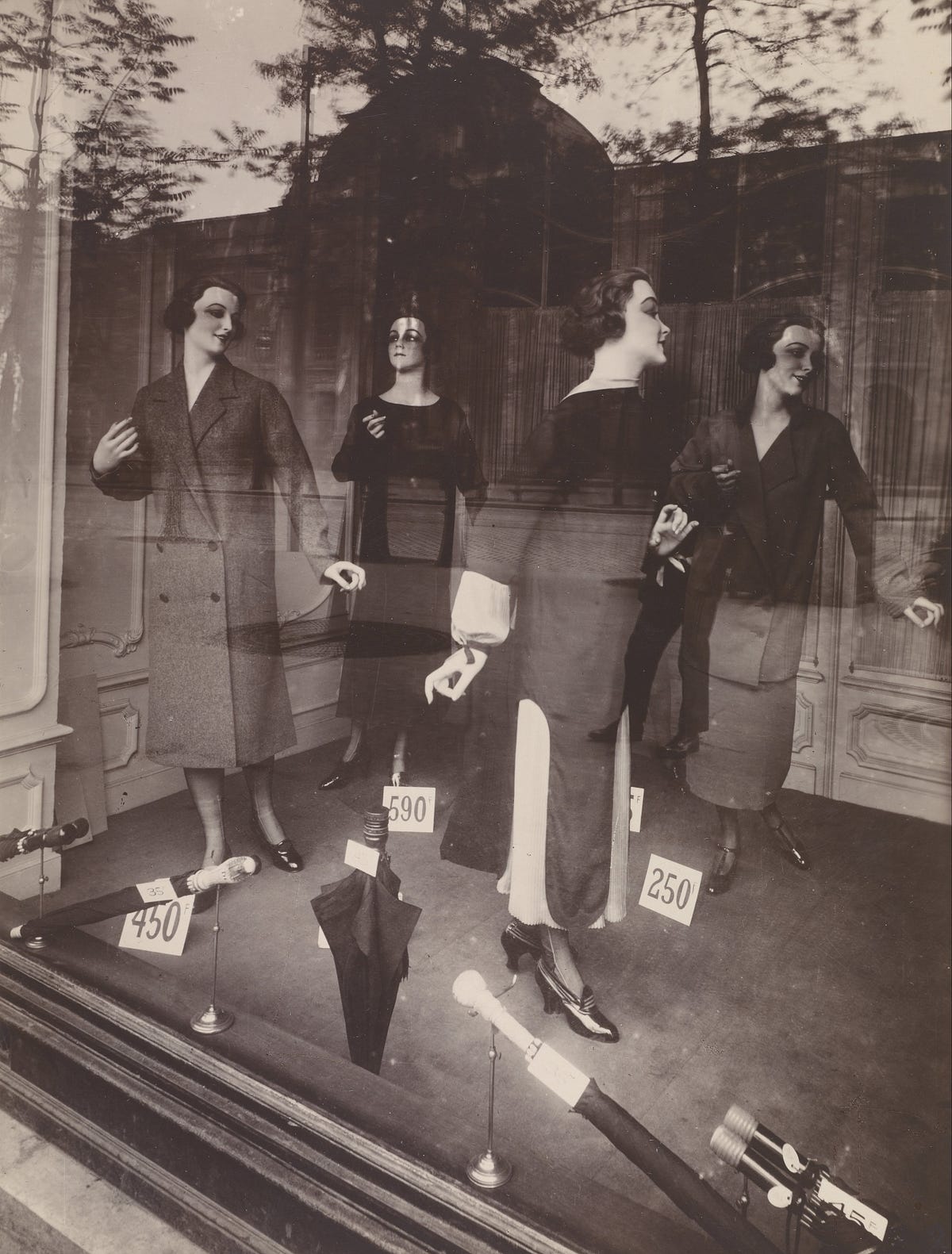

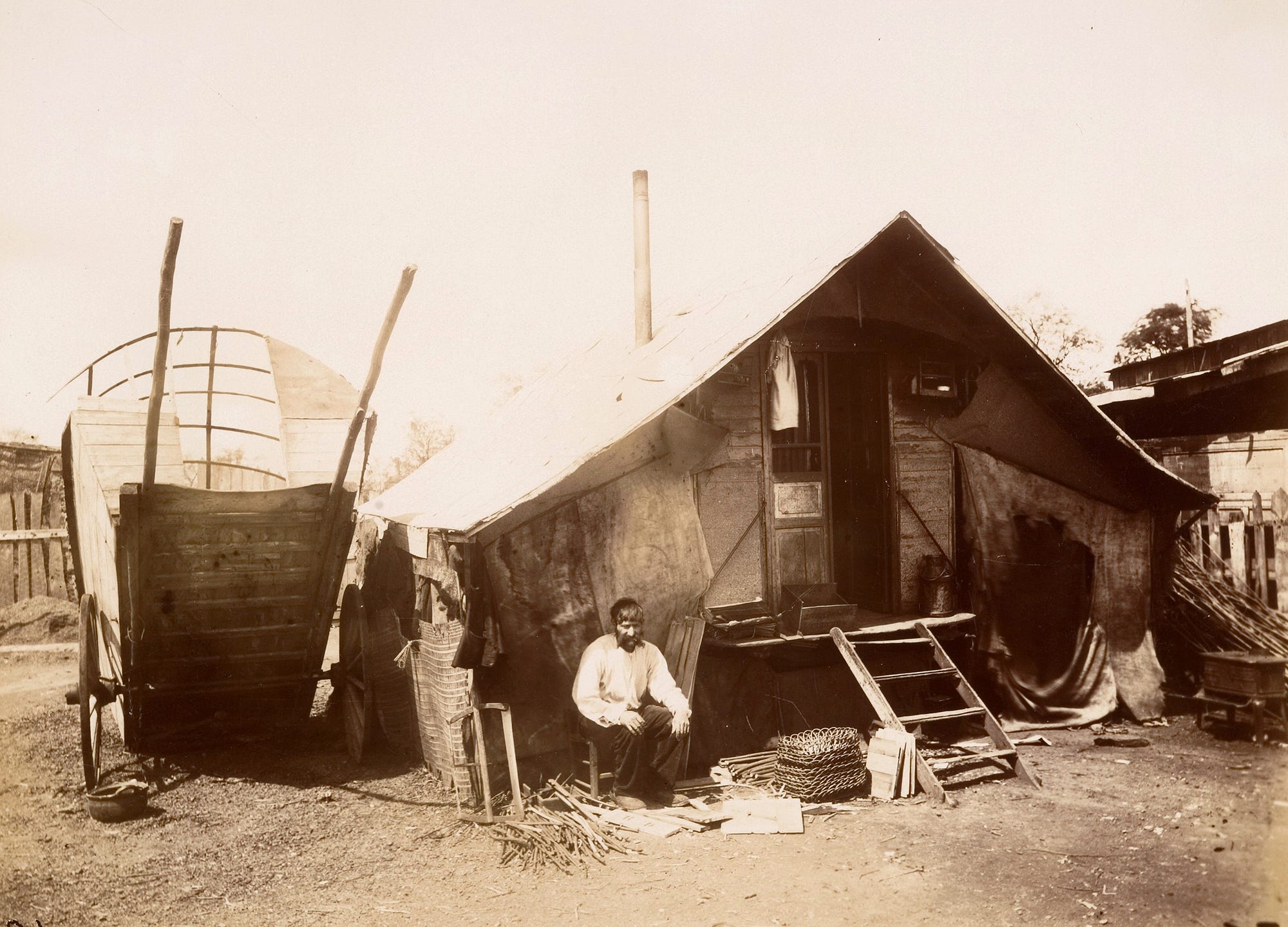

The city had evolved wildly and spontaneously through the centuries, its core tightly packed with ramshackle districts of working poor and the even less fortunate. Epidemics tore through the flea-ridden bedrooms and soot-stained halls, as did insurrectionary talk and proletarian plots. In 1853, Georges-Eugène Haussmann was tapped by Napoléon III to tear apart the darkest warrens of old Paris. For almost 20 years, his army of laborers fought centuries of messy, haphazard development with meticulous planning and precise execution. The city doubled in size with the 1860 annexation of its surrounding villages, re-creating them as parts of a cohesive, homogenous new metropolis, and the population verged on two million. Almost 20,000 buildings were destroyed under Haussmann, and hundreds of thousands of inner-city residents were displaced. The new apartments were filled by the middle class returning from the western suburbs, enchanted by this new postcard-perfect vision of a sophisticated and modern world-class Paris. The less fortunate were pushed further and further away from the heart of the city.

Atget trudged through the final years of redevelopment, its bureaucratic momentum outliving both Napoléon III and Haussmann, only to conclude in January 1927. He photographed the fading ghosts haunting street corners along the Seine, the ragpickers, prostitutes, and laborers. In time, the people faded away, and Atget intensified his scrutiny of the buildings themselves, the pockmarked walls and dark doorways, the details and fixtures from an earlier era. Though he was largely unknown during his lifetime, Atget had fans among city archivists and historians, architectural specialists and theater set designers, who bought his prints to remember the city that had once been.